Cluster Collections /

Collection Clusters

Joseph Doubtfire

Joseph Doubtfire

This essay is about clusters. Clusters formed by mussels, word clusters, sea plastic clusters, Lego clusters, collaged clusters and the clusters of collections forming in the work of artist Tina Dempsey.

MUSSEL CLUSTERS – collections of gravel and small pebbles, shell fragments and other organic odds and ends, which according to The Observer’s Book of Sea and Shore are nests formed by mussels (1968). These things are bound together with bysuss threads – strong organic matter that enable the mussels to anchor, either themselves to rock structures or to these formed collections. The bysuss threads give the clusters their delicate elasticity and articulated nature. Things within them are tied to one another, though are loose enough to shift, reform and reposition.

Tina Dempsey, who has gathered a small array of these mussel clusters, is also amassing collections in a cluster-like manner. Similarly joined and yet flexible, Tina’s collections are tied together with a common thread. They are connected to Tina, to her work, to the coast, to a process. They shift and reform, finding themselves recontextualised and repurposed via the artist-made object, a bookwork, a workshop, a conversation, an exhibition. Various forms of clusters are referred to throughout this essay and a word cluster has formed organically throughout its writing.

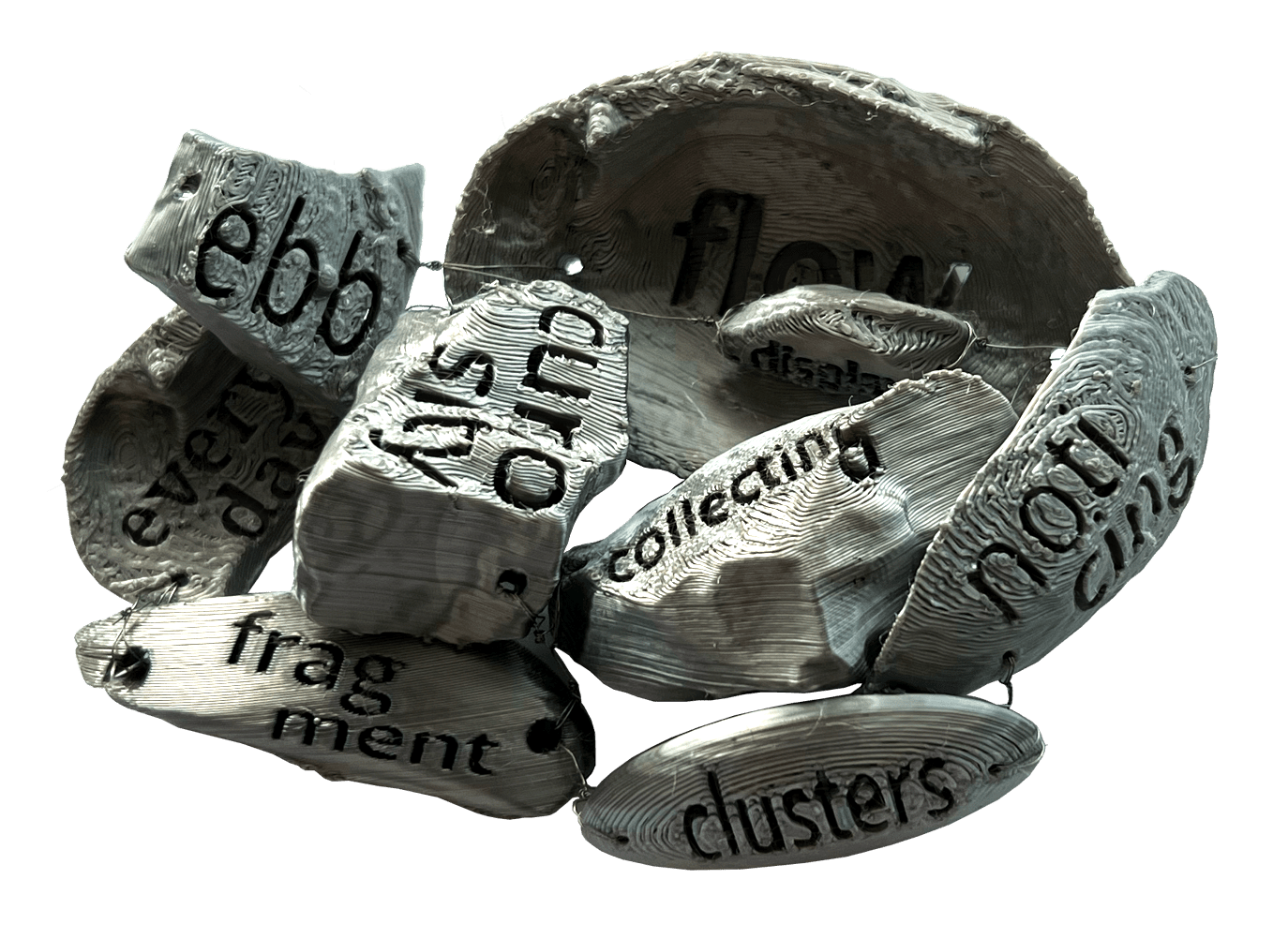

WORD CLUSTER – a collection of 3D printed words and phrases selected to represent the nature of Tina’s practice and collections, and an object mimicking the structure and movement of the mussel clusters.

In the preface to Strands, Jean Sprackland describes the beach she spent a year walking along as ‘stubbornly unknowable’, ‘never the same twice’ (2003: xi). Walking from Blackpool to Liverpool she acknowledges that this stretch of coast doesn’t ‘[obey] her at all’ (ibid). In the chapter Drifters, Sprackland describes coming across a door washed up on the strandline, its blue paint weathered and flaked by the water – reflecting on the strangeness of such a find, she describes the ‘indiscriminate way the sea takes things in and throws them back’ (ibid: 129). The way Tina’s collections are formed is similarly tidal, indiscriminate, and ultimately responsive. Within an art practice it’s difficult to dictate the journey, artists instead having to function within a level of ambiguity. Both Jean Sprackland and Tina Dempsey stumble upon things in the process of walking and the act of noticing informs the direction of their work. As you walk along the strandline, a collection of debris deposited by the tide – a line of stone, shingle, driftwood, shells, sea glass, plastic ear buds (long outliving their place on supermarket shelves) and all manner of other things are amassed – more temporary, less selected than a museum’s collection – more of a hoard, perhaps, but a collection, nonetheless. As a collection, the nature of a strandline is not dissimilar to the cluster, or even the sand mason tube (another one of the collection’s curiosities).

‘Canned life’ (1967) is the phrase used by Alan Kaprow to define museums’ understanding of the intersections of art and life, and their display. Linking them to ‘mausolea’ (ibid) he suggests stagnant spaces, showing objects taken out of circulation, shrines to the dead: objects, people, histories. It’s easy to see how museums might start to be perceived as celebrating ends, how objects taken out of circulation cease to be relevant. This idea seems contradictory of Tina’s collection however, which she discusses as an ‘alternative’ museum. Whilst Nikolai Federov asserts ‘the museum is the collection of everything outlived, dead, unsuitable for use’, he goes on to connect the museum with the idea of hope on account that they enable you to see the pure possibilities of their collections, that ‘there are no finished matters’ (2015). Unfinished matters captures the essence of Tina’s practice, which has no opportunity to become staid on account of the rapidity of things washing up on its shore and becoming another thread of the collection. The collection exists not only to be marvelled at, but to inform future actions.

Marion Endt-Jones in her essay Between Wunderkammer and Shop Window describes 16th and 17th century cabinets of curiosities as balancing ‘microcosm and macrocosm’, on account of their ambition of small-scale representation of the entire universe, through extraordinary oddities and objects (2013). Tina’s collections have strong ties to their local shoreline, where she walks and gathers. There are treasures from further afield, things that contextualise the local haul in a greater landscape. The collection champions Fleetwood and there is a sense of learning a place – in fact, some of the most unusual coastal finds have been found on Fleetwood beach, to the great surprise of geologists Tina is working with currently. Aside from Fleetwood-found treasures, things are acquired from travels further afield, picked-up, bought, made, and these stand to situate the close at hand in a broader context – balancing the macro/micro, the local/national.

Bound up with a sense of status, power, wealth, ownership, and colonialization, Wunderkammer owners had a general air of authority over the objects they collected, and over the representation of the places and people they came from. Also bound up in institutions or private estates, they demonstrated the power and wealth of their owners and were inaccessible to most people. Peripatetic, and already moving between community centres, an old hospital, and being disseminated through open-access workshops (rather than simply via art institutions), Tina is already ensuring the collection’s reachability. It sits in interesting dialogue with recent questions about quite how public our public institutions actually are. Perhaps most unusually for any sort of museum, you are encouraged to touch. Endt-Jones describes the glass vitrines used within museums and the Surrealist naturalia cabinets and the imagined touch they inspire. The glass display case, she states, facilitates ‘selection and classification’, imbuing objects with a sense of value. Objects in the collection might sit in glass cases, vitrines, vials, or petri dishes, though they are there to be taken out, touched, drawn, collaged, cast, examined under a microscope. For Tina, the collections inform the development of new work.

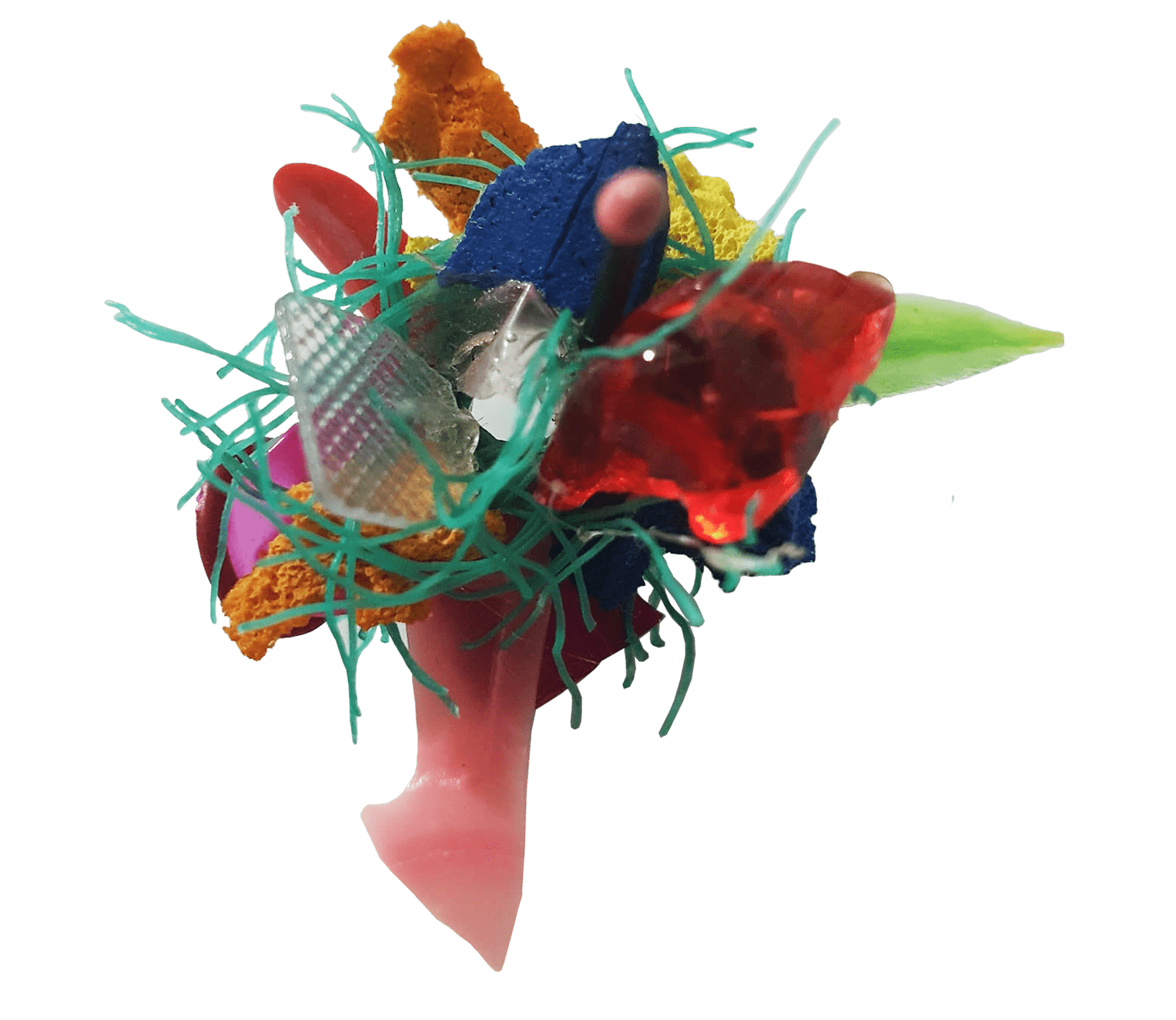

SEA PLASTIC CLUSTERS – collections of sea plastic, washed up on Fleetwood’s coastline, collected, both on account of their aesthetic value, though primarily to remove them from the coast. Beginning to collect them before knowing what to do with them, Tina cleaned, preserved, organised, and stored these objects – a colourful archive. Equally captivating and sinister, she takes these small, delicate fragments and binds them together, creating precious assemblages of lurid-coloured plastic. Their colour stands out against the natural objects in collections, with their subtle marks and soft tones. These plastic clusters have strong ties to Tina’s other work in collage and painting – with evident focuses on colour, shape, and play. Their plastic nature and vibrant colour has led to making them in Lego.

LEGO CLUSTERS – collections of colourful pieces of Lego, connected to create small, abstract constructions, which resemble the sea plastic clusters, and the mussel clusters in turn.

Jumping between clusters, you are able to see an artist joining the dots. These collections make visible the jumps between information, inspiration, and creative acts, as well as between the works themselves.

Collections of collections within Tina’s practice, the cluster-like acquisition process, seem to be an invitation – perhaps, to form your own collection clusters. As well as through noticing, finding, and purchasing, the collections are also amassed through people, their gifts, and creative responses. These things become part of the collection’s wider relevance, which starts to reflect not only Tina’s interests, but something about the people and communities that have encountered it. Gifts given so far: The Observer’s Book of Trees and Shrubs encasing dried and pressed specimens of each plant; concrete pebbles with painted flecks and an abstract painting on found wood; a driftwood parrot and a note detailing its place of finding and interest; a hag stone; a cyanotype of a cloud developed by moonlight. To a certain extent there is a gift economy at work here, with inspiring things being shared, and then responded to, acquired, and shared again. If as Mauss (2002) discusses, the gift is consumed in its use, rather than in a monetary exchange, then then gift of these collections is the way they make you want to observe, hold, feel them and to draw, photograph, paint, collage, collect.

We are discouraged from judging gifts on their monetary or exchange value, instead appreciating their sentimentality or thoughtfulness. It’s no wonder that these collections have inspired such thoughtful reciprocal gifts, on account of this ethos of generosity and sharing. These gifts are valued by Tina, not on account of exchange value, but of their relevance to her interests. Even making new collages from the packaging of the gifts demonstrates the responsive nature of her process. The circular and gift-like approaches to acquisition and making discount the idea of a central arbiter of a Wunderkammer collection, or the hierarchies within museological institutions, instead favouring dialogue and generosity.

As with the packaging-cum-collages, the way the mussel clusters have informed the sea plastic clusters and, in turn, the Lego clusters, is emblematic of Tina’s process. Something new catches the eye and gives her the next thing to focus on. The clusters are also an interesting analogy for her collections in their entirety, given how hard-won these finds were. The Sea Diaries are Tina’s notebooks, commonplace books of sorts, recording her coastal journeys, experiences and finds. In an extract of the Sea Diary she describes finally becoming aware of and intending to collect mussel clusters, and finding it impossible to do so. These notebooks document the experience of collecting, the sights, smells, sounds, textures, and the frustrations, the surprises. In them, things are found, pondered, researched, and learned about. The notebooks are a reminder of the wonder of childhood collecting. The desire to find mussel clusters aside, Tina seldom embarks on a walk with a shopping list. Rather, she is observant and responsive – or as she states, she “leaves it to the sea”.

Ubiquitous objects are prized on a level with rare finds. Large forms of fossil coral; a porpoise’s vertebrae; a devil’s toenail (scientific name – gryphaea); an extinct oyster fossil; a giant barnacle, a wasp’s nest, and a small selection of hard-to-find milk glass all sit aside a collection of minuscule pieces of soap. These are unusable remnants leftover after long periods of handwashing, archived with details of their use on small pieces of quality watercolour paper. These are commonplace items, though no less wondrous. Perhaps most striking in this context is their resemblance to shells or pebbles. Their slight differences in colour, soft pastel tones, the smoothness of their surface on account of the water erosion. There is an ambiguity, in this sense, between the natural and the made. And this calls to mind the philosophies of the Wunderkammers, in which you would encounter beautiful, natural treasures, alongside unusual inventions falsely presented as rare curiosities and oddities – famously, taxidermied mermaids, actually comprised of a monkey’s head attached to the tail of a fish. Not interested in the taxonomic display of things, instead Tina bounces about with disciplinary boundaries and the classifications of things. Not out of an interest in hoodwinking unsuspecting viewers but instead inspiring curiosity and creativity. The collections do not defy categorisation, but play with it, bend it.

As Tina learns the best spots for finding mussel clusters, clears more plastic from the coast, forms new sea plastic clusters and creates new Lego constructions, The cluster collections continue to accumulate. Collecting initiates a process, one that responds to things acquired and the nature of collecting itself. The process of collaging has become increasingly cluster-like, with recent works looking at collages as an accumulative gathering of material, rather than the curation of a pictorial plane.

CLUSTER COLLAGES – collages which look not at placement of material and paper fragments, but the simple combining and stacking of visual material, often watercolour paintings resembling collections of pebbles.

Tina’s practice, which is one of responsiveness and not knowing, is also one of careful selection, curation, iteration, and care. As with the nature of the mussel clusters, both Tina’s collections and the word cluster will continue to multiply, new fragments/words added as the practice shifts and adapts and as it forms its nest. Though perhaps more importantly Tina’s work will continue to grow its community, to reach out and connect with others. As well as bysuss threads being used by mussels to anchor themselves to small, pebbly nests, mussels also use them to anchor themselves to each other. The phrase ‘mussel cluster’ not only appropriately describes the small collections of gravel and pebbles, shell fragments and other organic odds and ends, the nests that individual mussels form, but clusters of mussels themselves, networks, communities.

References

(1968) Observer’s Book of Sea and Seashore. London: Frederick Warne & Co.

Endt-Jones, M. (2013) ‘Between Wunderkammer and Shop Window: Surrealist Naturalia Cabinets’, in: Welchman, J. ed. (2013) Sculpture and the Vitrine, Aldershot: Ashgate, 95-120.

Federov, N. (2015) The Museum, its Meaning and Mission. e-flux Journal (online). Issue 65, May 2015. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/65/336461/the-museum-its-meaning-and-mission/ [Accessed June 2015].

Kaprow, A. and Smithson, R. (1967) What is a Museum? A Dialogue. In: Alberro, A. and Stimson, B. eds. (2011) Institutional Critique: an anthology of artists’ writings. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Mauss, M. (2002) The Gift. London and New York: Routledge Classics.

Sprackland, J. (2013) Strands: A Year of Discoveries on the Beach. London: Vintage.